Liberal Democrats and electoral reform: a history

At an Islington Liberal Democrats Proportional Representation event in February 2020, Keith Sharp gave a (slightly personalised) account of the liberal fight for equal, proportional voting: the wins, the losses, the lessons and the current opportunities.

Origins and Beliefs

Electoral reform has deep, principled roots for Liberal Democrats.

The Reform Act of 1918 greatly extended the voting franchise (men over 21 were given the vote and women, albeit from age 30, had the vote for the first time). But it also saw the already-existing first-past-the-post (FPTP) narrowly defeat proportional representation (PR) / single transferable vote (STV) as the chosen UK electoral system.

The Liberal Party's response was swift. Electoral reform (STV) featured in its 1922 election manifesto and has ever since (as the Liberal Democrats since 1988) remained firm, if not always prominent, party policy.

We talk today of the need for party proportionality - percentages of seats at Westminster should match percentages of overall votes the parties receive. And that's right. Yet, while party proportionality is a vitally important result of a voter centric system, it is not the sole guiding value.

In a liberal society, power and agency reside primarily with the individual; and with the individual in her/his social context (such as family, neighbourhood, locality or community.) The job of the electoral system is to deliver demo-cracy (demos = people), not state-ocracy or even political party-ocracy. Party proportionality is a welcome result of a voting system which reflects the voters' preferences.

Of course - a point often made - electoral reform alone isn't a sufficient cure-all for our democratic deficit. Other important proposals include a written constitution, coherent devolution, votes at 16, a defined role for deliberative democracy, proper rules for holding any future referendums, Lords, local government.

But what can be more critical, in a functioning democracy, than the core relationship between electors and their elected representatives - defined by the way in which we elect and hold them accountable and the complexion of the resulting Parliament (or Council or Assembly)?

Stirrings - the '70s and '80s

The two elections of 1974 - when (in February) Labour won more seats despite getting less votes than the Conservatives; and a big jump in Liberal votes still left them with only a handful of MPs* - saw the first upsurge interest in electoral reform. (The earnest but in those days long-marginalised Electoral Reform Society (ERS) was so overwhelmed with public and media interest that staff took the phone off the hook to stop the incessant phone calls). And the 1975 European Referendum not only produced a healing near-unity in this country; it exposed the rigidity and voter-denial of FPTP as politicians of different parties and stripes cooperated according to their stance on Europe.

Literature sprang up in the '70s

Heady times… all this converted me from a latent to an active PR campaigner. I tracked down and, years before joining a political party, became a member of ERS. Reading the emerging literature on the issue I soon realised that it wasn't only a matter of seats matching votes. FPTP did not - could not - reflect late twentieth century social change. Without reform, voter disillusion and a sense of powerlessness was setting in. This was leading to a distrust of politics and its institutions; to a decay of respect for democracy itself. It was so obvious; and all it needed (so I thought, with the blind optimism of youth) was to alert people/politicians to the problem and reform would happen. I had a lot to learn about the addiction of power and cynical self-interest masquerading as public concern.

As for those warnings back then about disillusion and distrust? Look around you today. They have all come to pass…

In 1981, the Social Democratic Party (SDP - breaking from Labour over Europe) backed PR. After two elections in alliance with the Liberals where FPTP blatantly dissed the wishes of millions of voters and distorted the result**, the SDP and Liberals merged in 1988 into the Liberal Democrats, under Paddy Ashdown's leadership.

Achievements - the '90s and noughties

In the 1992 General Election, Labour suffered its fourth successive defeat. By 1994, Tony Blair became Labour leader. Ashdown abandoned 'equidistance', moving the LDs decisively towards Blair's Labour. In the mid '90s the two parties collaborated on political reform (known as the (Robin) Cook- (Bob) Maclennan agreement). A Lib-Lab pact was surely on the cards…

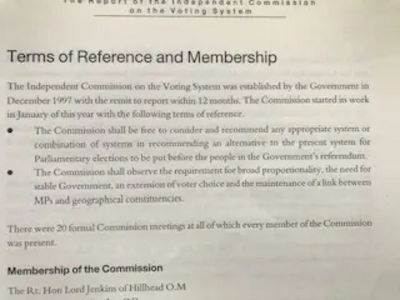

Not to be. The 1997 election, where just 43% voted Labour, nevertheless gave Blair a 179 seat majority. Labour did not need the Liberal Democrats. A Cook-Maclennan provision - an Independent Commission on the Voting System - went ahead but was still-born. Yet the Jenkins Commission as it is known (after its Chair, the great liberal Roy Jenkins) remains an ingenious, erudite, rewarding study. Its remit - proportionality, stability, geographic link, and… extended voter choice - still guides reformers.

Remit of the Jenkins commission

Failure to get PR for Westminster, however grievous, shouldn't mask the fact that significant progress was made. Devolution produced a parliament for Scotland and assemblies for Wales and London. The 1998 'Good Friday' agreement created devolved government in northern Ireland. The European Parliament electoral system was reformed.

Every single one of these innovations rejected FPTP in favour of PR - not necessarily the best systems available (Jack Straw's late decision to use 'closed regional lists' for the Euros was particularly regrettable) but the bottom line remained: FPTP was out, PR was in.

Scotland went further. A Lib-Lab Scottish government agreed to introduce PR (single transferable vote) for local Council elections from 2007.

I was lucky enough to be an Electoral Commission observer at the 2007 Scottish elections, spending a day visiting various polling stations and attending the overnight count in Galashiels. Everywhere I found quiet comfort with the voting system change. I remember in an Edinburgh cafe asking local customers if they knew about voting 1,2,3 rather than marking a cross. I didn't finish - 'You mean STV? Oh yes we know all about that. We're fine with it', said one lady, politely but

firmly.

So: what worked? There were three main conditions for progress and success:

- Negotiation (not referendums) in:

- Alliance or coalition (not 'equidistant'); with a

- 'Non-threatening' Labour ('90s Blair-style not '10s Corbyn-style)

And the voters? They had not clamoured for voting change, but once they'd got it they liked what they saw and were keen to keep it.

History need not repeat itself, but surely there are clues there as to what works…surely.

Reversal - the tens

A referendum on the Alternative Vote (AV) was the political reform concession for the Liberal Democrats on going into coalition with the Conservatives in 2010. This was only ever a Labour party commitment (in their 2010 manifesto - no-one else's) and yet AV became badged as a Liberal Democrat policy. Coalition partner, the Conservatives ruthlessly opposed it; policy-owners Labour were publicly split. AV was heavily defeated in the 2011 referendum.

Embarrassed, humiliated, defensive, the Liberal Democrats then hid away from electoral reform. While the Tories even advocated returning all public elections to FPTP, the LDs kept quiet, with the manifestos of 2015, 2017 and 2019 (see page 83 of the 2019 manifesto…) pushing reform to the margins.

2020 - out of despair comes…?

The December 2019 election was an unmitigated disaster. But out of it, maybe a renewal of hope:

- January 2020: a front-bench Commons spokesperson appointed (Wendy Chamberlain MP)

- Unite to Remain evolves into Unite to Reform, including electoral reform.

- The party proposes a pro-electoral reform motion for its Spring Conference (York, March 13-15).

- LDs for Electoral Reform, in York, stages a fringe meeting with Wendy Chamberlain and panellists from Wales LDs, Unite to Reform, ERS and Make Votes Matter. Theme: how to make reform happen this time.

Finally - the voter today

The downside (source: ERS research):

- Many voters think we already have a proportional system, so don't respond to calls for change.

- Voters get democracy; and non-democracy (dictatorships) as concepts. But they don't differentiate between levels or different shades of democracy. If there is a vote, it is democratic. End of story. So, saying 'it's not democratic enough' doesn't resonate.

The upside:

While voters may be not crying out for a new electoral system, in December 2019:

- 61% of voters said they were dissatisfied with the state of UK democracy (University of Cambridge)

- 32% of voters said they had voted tactically (Electoral Reform Society, p31)

- Only 25% of seats were regarded as marginal i.e. where any change of party was possible. (BBC website report) ***

Surely these numbers show that PR is hugely relevant to voters in 2020? They should guide us towards our call to action.

Keith Sharp has long campaigned for an equal, proportional voting system. He was an elected Council member at ERS for 20 years until standing down last December. He was an Electoral Commission observer at the 2007 Scottish elections (held under PR systems) and is currently Vice Chair of Liberal Democrats for Electoral Reform. Keith is also a member of the Make Votes Matter Alliance-Building Committee which engages with both party and non-party activist groups.

March 2020

Notes:

* In February 1974, the Liberals won 14 (2%) seats with 19.3% of the vote; in October an 18.3% vote share produced13 (2%) seats (Butler, p268/269)

** in 1983 the SDP/Liberal Alliance won 23 (3.5%) seats with 25% vote share. With just 27% of the votes, Labour won 209 (32%) seats (Butler p269)

*** In fact, only 79 seats (12%) of seats changed hands (Electoral Reform Society, p34)

Sources:

Voters Left Voiceless: Electoral Reform Society (March 2020)

British Political Facts: David and Gareth Butler, Palgrave Macmillan (10th edition 2011).